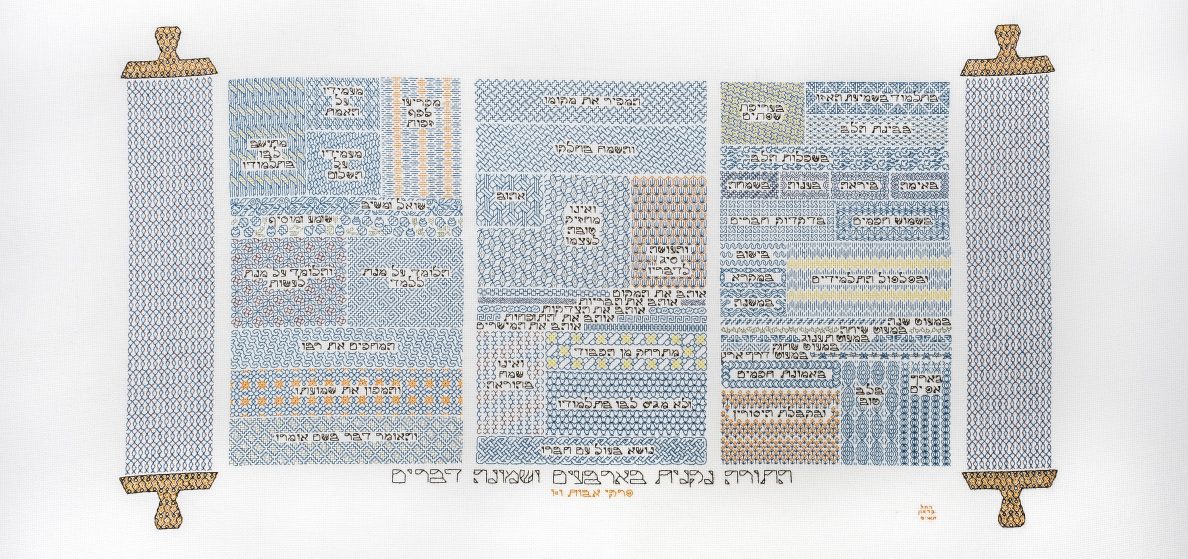

Pinhas 5783 Rachel Braun https://www.rachelbraun.net

This week’s parasha, Pinhas, includes a census of the fighting troops of the Israelites. This is a timely effort. Many Israelites have been killed in the plague following their involvement with Midianite women, the time for entering the Land is near, and apportionment of the Land by tribe will ensue. But the peculiar naming of tribal groupings in this Census provokes some interesting commentary on violence against women.

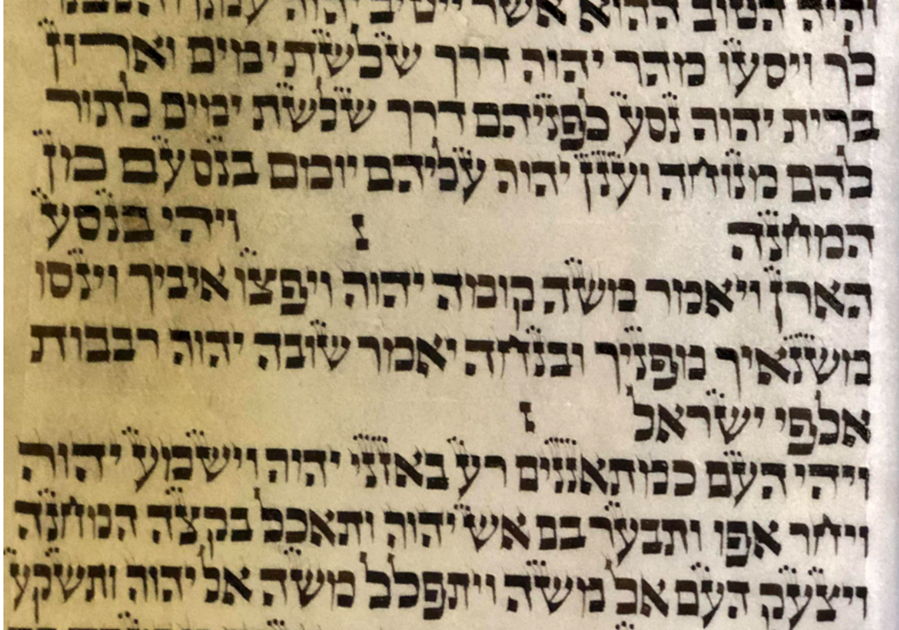

Here’s some of the text (Numbers 26:1-2, 5-6):

(snip)

It’s odd that the descendants’ names are repeated: “of Enoch, the clan of the Enochites”, etc. It’s like saying “The Israel Olympic team’s gold medal in rhythmic gymnastics at Tokyo 2020 was won by Israeli Linoy Ashram.” Hadn’t we already established that she was Israeli earlier in the sentence?

A common observation is that these tribal names (haHanokhi, haPallui) require two appended letters, yud and hey. These letters represent Yah, a name of God. Why has God chosen to wrap God’s name around these communities?

Rashi explains:

Essentially, Rashi argues that the heathen nations disparaged Israel’s tribal integrity by suggesting that the Egyptians, even as they exerted control over the bodies of Israelite men, surely shaltu, ‘overmastered’, the Israeli women. “Wow!” I thought as I first encountered this text. The tradition is acknowledging the use of rape as a tool of subjugation and war, a condition common to enslaved peoples all around the world, in past oppressions and still now.

God’s response, though, is perhaps not so “woke”. On the one hand, God is protecting these offspring by attesting to their fathers that the children are, in fact, legitimate tribal members. The source Rashi cites, Shir Hashirim Rabbah 4:12, describes the lengths to which God goes to secure their standing:

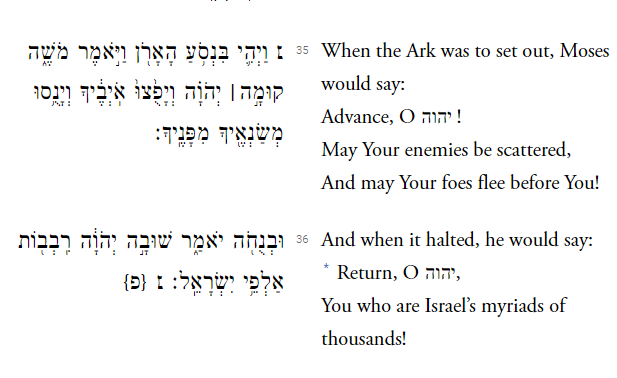

| אָמַר רַבִּי פִּנְחָס בְּאוֹתָהּ שָׁעָה קָרָא הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא לַמַּלְאָךְ הַמְּמֻנֶּה עַל הַהֵרָיוֹן וְאָמַר צֵא וְצוּר אוֹתָן בְּכָל קִטּוֹרִים שֶׁל אֲבוֹתָן, עִקַּר אֲבוֹתֵיהֶן לְמִי הָיוּ דוֹמִין לִגְדוֹלֵי הַמִּשְׁפָּחוֹת, הֲדָא הוּא דִכְתִיב לִרְאוּבֵן (במדבר כו, ז): מִשְׁפְּחֹת הָראוּבֵנִי. אָמַר רַבִּי הוֹשַׁעְיָא רְאוּבֵן הָראוּבֵנִי, שִׁמְעוֹן הַשִּׁמְעוֹנִי. אָמַר רַבִּי מָרִינוֹס בְּרַבִּי הוֹשַׁעְיָא הָא כְּמָה דְתֵימַר בָּרוֹנִי סַבְרוֹנִי סִיבוֹיִי. רַבִּי הוּנָא בְּשֵׁם רַבִּי אִידֵי ה”א בְּרֹאשׁ הַתֵּבָה וְיו”ד בְּסוֹפָהּ, י”ה מֵעִיד עֲלֵיהֶם שֶׁהֵם הֵם בְּנֵי אֲבוֹתֵיהֶם. | Rabbi Pinḥas said: At that moment the Holy One blessed be He called the angel appointed over pregnancy and said: Go and shape [the children] with all the features of their fathers. Who did the fathers themselves resemble? The paterfamilias of the families. That is what is written regarding Reuben: “The families of the Reubenites [haReuveni]” (Numbers 26:7). Rabbi Hoshaya said: Reuben, Reubenite [haReuveni], Simeon, Simeonite [haShimoni]. Rabbi Marinos ben Rabbi Hoshaya said: Like you say: Baronite, Savronite, Sivoyite. Rabbi Huna in the name of Rabbi Idi: Heh at the beginning of the word and yod at the end; God [yod-heh] attests for them that they were indeed the sons of their fathers. |

God indeed manipulates the fetuses’ bodily features and wraps two letters of the Divine Name around their houses to establish the parentage of Israelite men. Rashi upholds this claim by citing Psalm 122:4, characterizing God’s actions as an eidut le’Yisrael, a testimony to Israel, to translate the words more plainly than the JPS below:

I am pleased with the Divine efforts, but perhaps less with the motivation. Naturally, the fathers will feel more committed to children not conceived in rape, to whom they can pass on tribal privileges. So far so good. But the hush-hush changes in-utero don’t address a more modern perspective: must sexual violence against women be cloaked in secrecy?

Still, the Divine modification of fetal features addresses an important psychological and emotional challenge facing the mothers. I recall, from years ago, a photo essay of Rwandan Tutsi rape victims who bore children of their Hutu rapists. The mothers invoked the difficulty of raising sons who, as they approached adolescence, bore facial similarities to their rapists and torturers. The photographer likely was Jonathan Torgovnik, an Israeli-born son of Holocaust survivors. I couldn’t locate the original article that I read long ago, but some related links are provided in notes at the end.

Returning now to our text from Numbers – while God’s solution does not address the women’s emotions, continuing health problems, and potential for ostracism, it does accord these raped Israelite mothers a layer of visual protection and community inclusion that the Rwandan mothers struggle with.

Finally, I had occasion recently to re-read Gimpel the Fool by Isaac Bashevis Singer (1953). Saul Bellow’s translation may be read at this link.

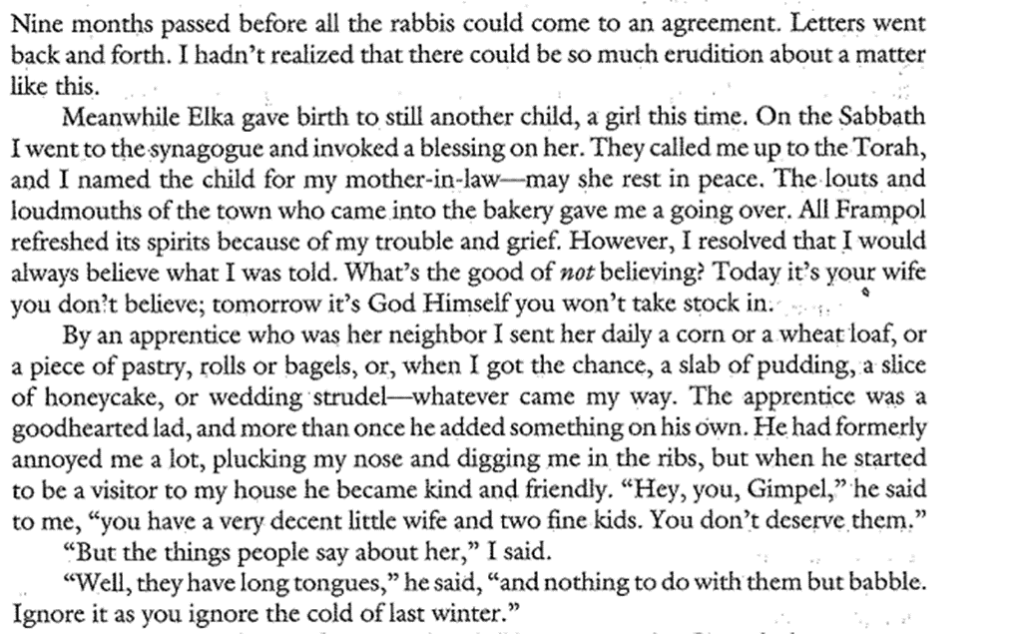

In the story, Gimpel is a retiring, trusting, long suffering “anti-hero” character, propelled by his town to marry Elka, a woman of questionable integrity who bears children who are not Gimpel’s. Deep in his heart, Gimpel knows what is happening, but even with the townspeople of Frampol mocking him and his own apprentice cuckolding him, Gimpel tries to accept the children as his own. Here is an excerpt:

Gimpel finally leaves his family after Elka’s death, becoming an itinerant and reflecting that our world is profoundly one of deception. In the final paragraph of the story, Gimpel muses:

In parashat Pinhas, perhaps God’s role in deceiving the Israelite tribal fathers is a bit of surrender akin to that experienced by Gimpel: an effort to rectify — but still a resigned acceptance of — injustice in the world.

——————————————————————

Notes: the work of Jonathan Torgovnik in Rwanda can be surveyed here: