The period between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur is “Aseret Yemei Teshuva” – the ten days of Repentance. The intervening days between these holidays have a special name — “bein Kesseh l’Assor” – between the covering (of the moon) and the 10th (Yom Kippur, whose date is 10th Tishri).

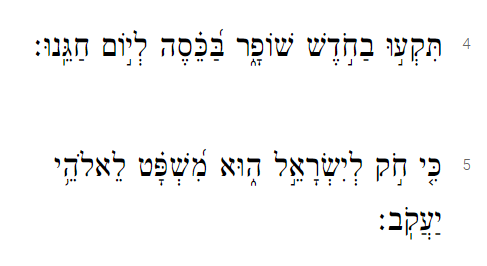

Why is Rosh Hashana associated with Kesseh, covering? The interpretation arises from Psalm 81:4-5, which read:

“Blow the shofar at the New Moon, a covering for the day of our feast; for it is a statute for Israel, a judgement for the God of Jacob.”

According to ibn Ezra, Verse 4 uses the word for covering to portray the darkened presentation of the New Moon, and verse 5 connects the New Moon to judgement.

Indeed, many of us experience the New Moon, Rosh Hodesh, as a mini Yom Kippur.

The Talmud in Rosh Hashana 8b specifically identifies this particular New Moon as Rosh Hashana, because of the promise of judgement.

Additionally, verse 4’s reference to yom hageinu, the day of our holiday, also supports the association with Rosh Hashana, as other Biblical festivals such as Sukkot and Pesah occur mid-month.

Thinking again about the phrase, bein kesseh l’Assor, I find this metaphor most stimulating. The lifting of the “covering” of the moon results in a visible moon on Yom Kippur, but not due to the moon’s own production of light, but because of its reflection of the sun.

I see this related to the concept of zekhut horim, the merit of our forebears. Will we act in the next year in a way that honors and reflects them, whether they are the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of our tefillot or loved ones we will remember at Yizkor?

As part of our teshuva, can we imagine that a successful goal of teshuva in the next year would be, like the moon, letting others shine THROUGH us, opening ourselves to others’ light and reflecting and amplify their voices and lived experiences?

Turning back to text, now, I think about other associations of moon and sun. In Talmud tractate Hullin 60, the moon is dismayed that despite the creation of two “great lights” in Genesis, it clearly has become the lesser light. Isaiah (30:26) imagines a Messianic age where the moon is restored and “the light of the moon shall become like the light of the sun”:

Jewish feminist midrashists find this a metaphor for the equality of women (represented by the cycling moon) and men (represented by the more prominent sun).

So perhaps another goal for our lives after this period of bein kesseh l’Assor is the pursuit of equality.

Tzom kal to all who are able to fast, and Gemar Hatimah Tovah — may we be inscribed for a good year, 5784.